“I believe today, when darkness is trying to overwhelm truth with full strength, then if nothing else, self-respecting Punjab, like a lamp, is challenging the darkness.” These poignant words of slain activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, from a speech in 1995, resonate throughout the 70-minute documentary Punjab Disappeared.

The film was screened at Jawahar Bhawan auditorium in New Delhi on April 26. It focuses on the ramifications of state violence and the resilience of the people of Punjab, decades after the insurgency in Punjab was successfully managed.

The film is stitched together using montages of testimonies, moving images of victim-survivors, the presence of the disappeared in photographs they carried and vignettes of violence from Manipur, Chhattisgarh and Kashmir. The viewer is guided by the voice of director Jaswant Kaur who narrates the decade long journey of documenting human rights abuses by the Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project (PDAP).

The documentary is a condensed form of a massive archive which has recorded over 8,000 cases of enforced disappearances. It is a brave attempt at privileging voices which have been systematically ignored: the narrative of victim-survivors over alleged perpetrators.

Mass illegal cremations in Punjab

I have written earlier on the role of NHRC in relegating social suffering of thousands of families and the role of alleged perpetrators to the sphere of invisibility. Instead, the Commission, through its final order in the Punjab Mass Illegal Cremations case, envisaged the prevalence of normalcy and peace in Punjab. It said, “both the State Authorities and the citizens should treat this order as an application of balm to whatever wounds were still left.”

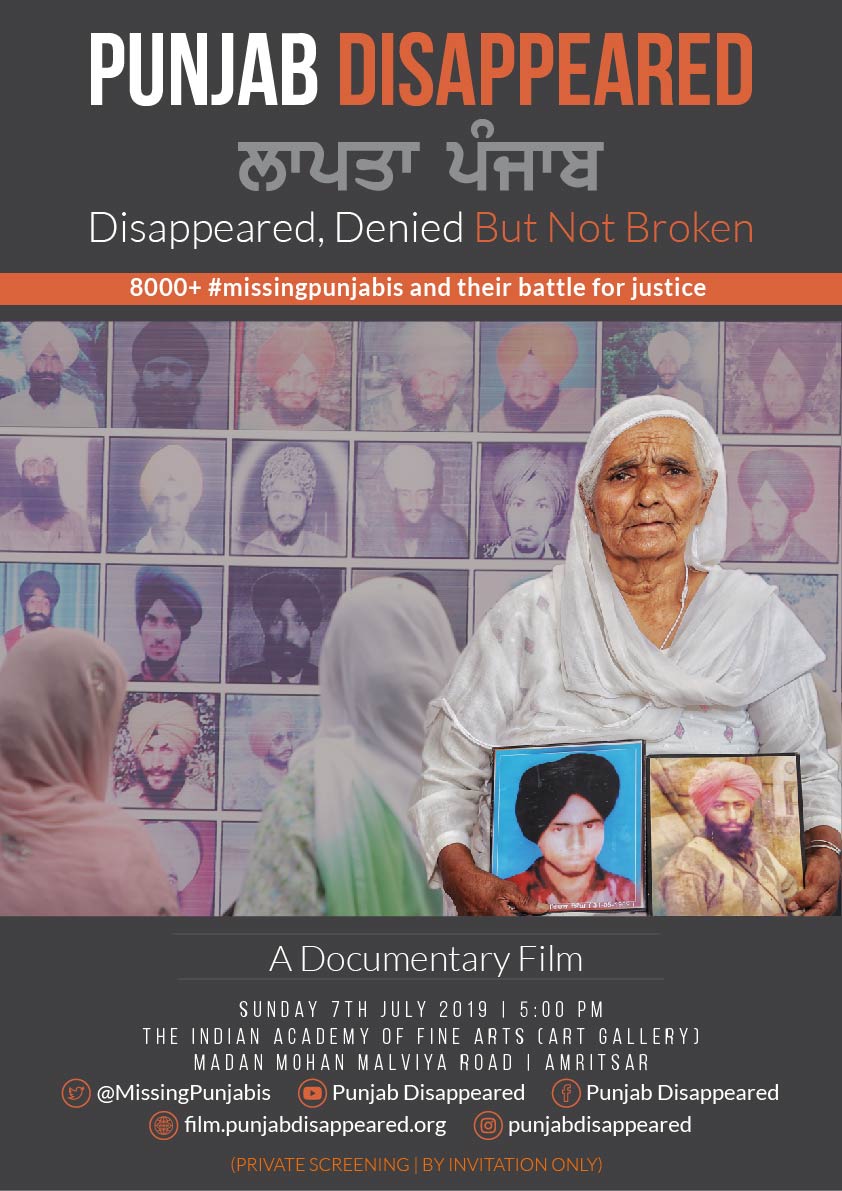

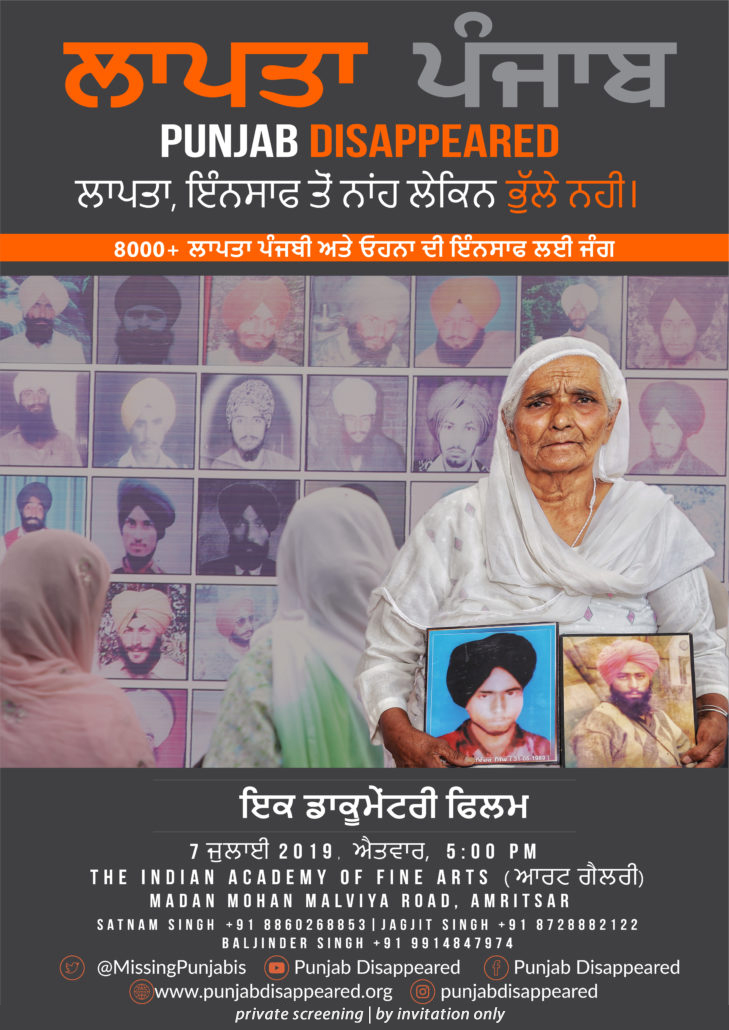

A Poster for Punjab Disappeared. Credit: Punjab Disappeared/Facebook

Through this documentary, the people of Punjab respond to institutions of the country by reiterating that the pain from their wounds lingers: compensation is not an alternative to justice, but an important component of it. They remind us that their lived experience, memories and struggle are not a footnote but an important chapter which profoundly impacts their life.

Documentation of mass atrocities, decades after its occurrence, is colossal and equally hard due to limited resources, aged relatives and police officers who continue to wield influence. Nevertheless, the PDAP has achieved what Colin Gonsalves, a senior advocate in the Supreme Court calls, “the most important human rights documentation work emerging out of India”.

In the footsteps of Jaswant Singh Khalra, the PDAP perused the records at cremation grounds which provided important evidence that coalesced with victim and survivor testimonies. The testimonies reveal how Sikh men were abducted from their homes, farms, workplaces, taken off buses, motorcycles, scooters, and never seen again. The families remember dates of the abduction of their loved ones, names of police officers and the police station that the “raiding party” came from.

These details, when read alongside the dates and police stations provided in the RTI responses of the record from Municipal Cremation Grounds, substantiate the claims of families. It shows the glaring probability that their relatives were eliminated in an extrajudicial encounter and cremated unceremoniously after being “unclaimed”. Since the dead bodies were not returned and no death certificates were issued to the families of those killed, the circumstances of their deaths remained ambiguous.

Perhaps it is this violence of ambiguity, the trauma of not knowing what happened to a loved one and the seemingly never-ending wait at the doors of justice which made advocate Rajvinder Singh Bains ask, “which pain is longer?”

One of the reasons why the dead bodies of those killed were not returned to the families was due to the probability of unfavourable outcomes. Advocate Brijinder Singh Sodhi recounts that the pervasive use of torture during interrogation was so much that undertrials would be carried by another person in their arms so that they could appear for court hearings. It is important here to remember that despite admitting that 194 people were killed while in the Punjab police’s custody, the NHRC did not take cognisance of reports and findings of Physicians for Human Rights and Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture.

If the bodies were returned, the families would photograph them and want another post-mortem report which would make the entire edifice of an “encounter” fall.

The film is most compelling when it connects the struggles for accountability and justice across landscapes of conflict. Victim-survivors and activists from Kashmir, Chhattisgarh, Manipur and Punjab use colloquial expressions of zulm, atyachaar, tashadat, yatana: oppression and anguish to describe their lives in militarised regions.

To ensure the non-repetition of these crimes, Manipuri activist Babloo Loitongbam, stressed the importance of a united struggle so that the “hegemonic structures of the Indian state can change”. The patterns of military and police excesses in Manipur mirror those in Punjab and so do the long legal encounters which people have to endure in the hope for justice.

Different bureaucratic and judicial encounters in the cases of mass violence, however, have largely coalesced around institutional impunity. It is further deepened through a policy of awards and promotions.

The women confronting state violence

It is the women who have challenged this juggernaut by negotiating through masculine spaces like torture centres, police stations and army camps. They have weaponised their vulnerabilities under grave risks and spoken out against rape, extrajudicial executions and disappearances. Parveena Ahangar and members of the Association of Parents of Disappeared People have publicly mourned and protested against the enforced disappearances in Kashmir on the tenth of every month in Srinagar.

In Chhattisgarh, both Adivasi men and women have been subjected to rampant sexual violence and extrajudicial executions. Soni Sori pointed out the precarity of Adivasi men in approaching police officials who can be apprehended without evidence. It is the women who march long distances in large number and gherao police stations to make themselves heard.

Unlike Punjab where bodies were not returned to the families, in Chhattisgarh, bodies of those killed in fake encounters are returned to the kith only when they sign an affidavit stating that their family member was a Maoist. Thus, the state seeks legitimacy for unlawful acts through coercion, extending its control of the killable or encounterable body.

In Punjab, Paramjit Kaur Khalra’s indomitable spirit has guided the human rights movement for over two decades. In her own words, “Punjab will never forget what happened to its people in the name of counter-insurgency”. The documentary highlights how the scars of violence have an inter-generational effect.

On Friday, Tejbir Kaur whose parents were shot dead in police custody in 1992 when she was only ten months old, said:

“I was raised in an orphanage. They told me I was with my parents when they were apprehended by the police. I was handed over to a lady constable after my parents were killed. I know very less about them, but I want their killers punished.”

In my various conversations with the documentation team in the summer of 2018, the “right hand” of the PDAP, as Barrister Satnam Singh Bains called them, an overarching sentiment was that of “chardi kala” or the Sikh tenet of high spirits in every endeavour.

In retrospect, it is this resilience which has kept Satnam and Jaswant going. “Many people told us, why are you doing this work? It will lead to a “revival” in Punjab,” said Satnam. “I say, yes. Yes, it will revive the hope for justice”.

Preetika Nanda has worked with the Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project and researches violence, memory and resistance in ‘post-conflict’ Punjab.