Vikas Dubey’s Killing Reminds Punjab of 2,000+ ‘Disappearances’ During Insurgency

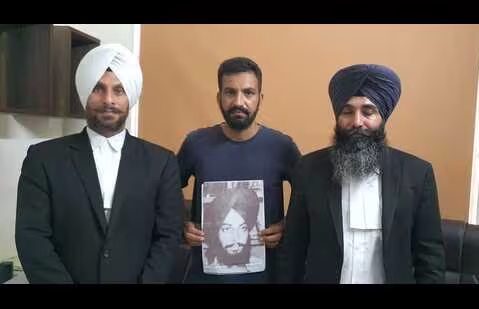

A poster for Punjab Disappeared, a documentary on enforced disappearances in Punjab.

Chandigarh: As the country debates the truth of the Uttar Pradesh police’s official narrative of gangster Vikas Dubey’s death – a car accident, an attempted escape and police firing in self-defence – which some feel is an example of a thriving culture of extrajudicial killings masquerading as encounters at the cost of rule of law, hundreds of families in Punjab have been living with the same ordeal for years.

Punjab shows how coercive methods, widely perceived as a necessary evil to end the insurgency that prevailed in the state between the 1980s and the mid-’90s, led to the forced disappearance and alleged killings of apparently thousands of people who no one knows for sure were actually guilty of any crime.

Even though the human loss of what had happened that time is irreparable and the affected families continue to suffer, there has still been no thorough probe into how many actually went missing during those turbulent days.

Whatever is available in the public domain is the result of either a Supreme Court-monitored probe by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) in the 1990s which centred on Amritsar, or the claims of different NGOs, one of which recently filed a petition in the Punjab and Haryana high court seeking the appointment of a judicial commission to investigate extrajudicial killings all across Punjab.

‘Flagrant violations’ but only partial investigation

The Supreme Court (SC) first took notice of the disappearances in Punjab on November 15, 1995, in the wake of the abduction and murder of Amritsar-based human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra. Before his death that September, Khalra had charged the Punjab police with clandestinely cremating 2,097 dead bodies in Amritsar, Taran Taran and Majitha areas.

The SC directed the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to inquire into Khalra’s abduction and the facts of Khalra’s claims of secret cremations by the police.

Subsequently, the CBI probe between 1995 and 1998 established several cases of extrajudicial killings and fake encounters. The agency filed charge sheets in 44 cases and also charged nine police personnel with Khalra’s abduction and murder. Six of these people were later given life sentences.

The trial is still pending in most of these cases due to legal loopholes. But a major drawback of the investigation at that time was that the CBI probe did not expand the investigation to other parts of Punjab, even though the apex court in its order on December 11, 1996, acknowledged the matter as a “flagrant violation of human rights on a mass scale”.

Even the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), which was brought in by the SC to compensate the affected families in the cases where dead bodies were identified in the CBI probe, did not enlarge its proceedings to a pan-state level.

Several members of civil society asked the NHRC to invite applications from the legal heirs of disappeared cases all across the state. But in its order dated October 16, 1998, the commission held that the scope of its inquiry under the SC directions was limited to only those illegal killings that culminated in the cremation of 2,097 bodies in and around Amritsar that was the subject matter of the CBI inquiry.

On February 15, 2001, a plea was once again raised by the counsel of affected families for the NHRC to seek clarification from the SC about the scope of inquiry, but the commission did not consider it.

In its report to the SC, the CBI indicated that 585 dead bodies that had been secretly cremated were fully identified, 274 partly identified and 1,238 unidentified.

In its detailed November 11, 2004, order on this issue, the NHRC held that the human rights of 109 persons who were admittedly in the custody of the police immediately prior to their deaths stood invaded and infringed when they lost their lives while in the custody of the police, thereby rendering the state vicariously liable.

The order stated:

“There is a great responsibility on the part of the police and other authorities to take reasonable care so that citizens in their custody are safe and not deprived of their right to life. The state of Punjab is therefore accountable and vicariously responsible for the infringement of the infeasible right to life of those 109 deceased persons as it failed to safeguard their lives and persons against the risk of avoidable harm.”

The order ended with a quote from Mahatma Gandhi: “Peace will not come out of a clash of arms but out of justice lived and done.” But several questions still remained unanswered.

NGOs do the investigating

Ensaaf, a US-based non-profit organisation that has been working since 2004 on the issue of police impunity with a special focus on Punjab, has so far claimed on its website that Punjab had 5,302 cases of forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

The NGO’s co-founder, Sukhman Dhami, said that they compiled their information based on primary interviews with affected families, exposing the widespread and systematic extent of the abuses that took place at the cost of the victims’ right to life and right to a fair public trial.

“Our aim in compiling this information is so that these things are not repeated and the state fixes accountability on the perpetrators of the crime,” said Dhami. “The total absence of accountability for these atrocities has entrenched a culture of impunity and ‘encounter justice’ all across the country.”

Meanwhile, Chandigarh-based NGO Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project (PDAP) released a report in December 2017, claiming to have identified 8,257 persons who disappeared from 1980 to 1995 from all across the state and were also cremated as unidentified and unclaimed bodies.

PDAP’s convener, Satnam Singh Bains, told The Wire that their research is basically an extension of the initial exposé by human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, covering alleged extrajudicial executions and illegal cremations beyond Amritsar, over 26 cities and tehsils of the state.

“We collected data from cremation grounds and municipal bodies where dead bodies were burnt as unclaimed and unidentified at that time by the police authorities. We also accessed around 1,200 FIRs of reported encounters out of which 274 FIRs matched exactly with the dates of illegal cremations obtained from cremation grounds,” he said.

Bains pointed out that most of the encounter FIRs tell a strikingly similar story in which police officers were left unscathed during the encounter, while the person in their custody invariably died in the firing.

“Most of those who went missing, we believe, fell prey to the vicious environment prevailing that time where police officers were being incentivised with easy promotions for killings,” said Bains. He added that even if many of them had links with insurgency, they deserved a fair trial under the constitutionally framed criminal justice system.

PIL seeking wider investigation pending in high court

Last November, the PDAP filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Punjab and Haryana high court, asking for an independent judicial commission under a retired Supreme Court or high court judge to investigate secret killings by the police in the entire state and even outside of it. The PIL also asked for compensation and rehabilitation for the families of the victims of secret killings.

The petition placed its reliance on the Supreme Court’s 2017 intervention in the case of the extrajudicial killings and disappearance of 1,528 persons in insurgency-ridden Manipur over two decades, in which it directed the CBI to investigate the matter. It also referred to the SC’s legal proceedings in Jaswant Khalra’s case.

The high court is still exploring the grounds on which the SC ordered the Manipur probe and will next hear the matter in September. Meanwhile, the recent orders pronounced by trial courts in CBI-led investigations are eye-openers.

In its 2018 ruling on the 1992 disappearance case of 16-year-old Harjit Singh from Amritsar district’s village Sultanwind, a special CBI court in Mohali held that the sole purpose of his abduction was to eliminate him.

The court awarded life sentences to two retired sub-inspectors (SI), Narinder Singh Malhi and Gian Singh. It said that all the directions of the Supreme Court were disobeyed before the police arrested the deceased and no explanation of any kind was given even later by the accused as to where Harjit Singh was and what happened to him after his abduction.

“The said child has not seen the light of the day after his abduction. Thereafter what happened to him is not known. Whether he is dead or alive is a mystery his parents try to solve every day. In these circumstances, it is not a fit case where leniency can be shown to the accused,” read the court order.

Another CBI court order in 2018 exposed the 1992 fake encounter of 15-year-old Harpal Singh of village Palla in Amritsar. The FIR registered by Amritsar’s Beas police station on September 18, 1992, claimed that Harpal had been killed in a gun battle after he escaped police custody.

The CBI court, while awarding life imprisonment to Raghbir Singh, the then station house officer (SHO) of Beas police station, and Dara Singh, a then sub-inspector, held that the police party’s claim to have fired 217 bullets during the encounter was fabricated as the empty cartridges had not been recovered or seized during the encounter.

The order said it was strange that the boy’s body was cremated as unclaimed when his identity was well established by the police and there was no record to show that his family members had refused to accept his body. Also, none of the bullets alleged to have been fired by the deceased is stated to have hit any of the police members or their vehicles, although it was claimed in a police report that the firing was started by the deceased.

“From the given facts, it is clearly proved that the encounter in which the deceased is stated to have been killed is not genuine. The accused tried to prove that the deceased was a terrorist but nothing has been produced to show that he was involved in any criminal activities,” the order stated.

The court observed that it might have believed the police version had the police shown that even a single bullet had hit any of the police vehicles or police officials. It added that the police version might also have been believed if the empty cartridges had been recovered. “In absence of it, it can’t be held by stretch of any imagination that the deceased was killed in encounter by the police,” the court order said.

Another CBI court order in 2019 awarded life sentences to a retired DSP, Harjinder Pal Singh, the then SHO of Ropar (Sadar), in the fake encounter of two men, Kuldeep Singh and Gurmail Singh.

An FIR registered on February 1, 1993, stated that the accused policeman was taking Kuldeep and Gurmail to recover arms when they were ambushed by unidentified persons near Bhadal village in Ropar. The policeman claimed then that in the crossfire between the police and the attackers, both Kuldeep and Gumail were killed. The police even cremated them, declaring their bodies unidentified.

The court ruled that the action of the accused policeman cast serious doubt about his version. Had the encounter happened as alleged, the accused policeman would have certainly taken into possession the empty cartridges of bullets fired by the police party.

The court also held that dead bodies were not handed over to family members, but cremated as unidentified though the police had identified them. The post mortem report had mentioned the names of the deceased. Similarly, the FIR also had their names and addresses.

“It is duly proved that both the deceased were in custody of SI Harjinder Pal Singh. The story put forth by him is false and thus it is held that the deceased were tortured and killed by him. Therefore he committed the offence under section 302 and 218 IPC,” stated the order

Former DGP booked in 1991 disappearance case

On May 6, in the middle of the nationwide lockdown, the Punjab police booked Sumedh Singh Saini who had served as a director general of police between 2012 and 2015 in the 29-year-old case of the disappearance of a Chandigarh youth, a son of a then serving IAS officer.

The FIR against Saini was filed in Mohali by Palwinder Singh Multani, regarding the alleged abduction and disappearance of his brother, Balwant Singh Multani, in December 1991.

Saini was charged in multiple crimes including kidnapping or abducting in order to murder; wrongful confinement; and voluntarily causing hurt to extort confession. He initially got out on anticipatory bail on May 9, but when his case was transferred to another court this month, his bail was cancelled on July 10.

Saini’s counsel told the media that he was being targeted for his anti-corruption drive when he was the head of the state’s Vigilance Bureau. Meanwhile, the police’s next course of action is awaited.

The case against Saini may prompt people to think that justice is finally catching up with big shots who may have been involved in dubious activities. But senior journalist Jagtar Singh does not believe this. He said the root cause of the entire problem is that the state never acknowledged constitutional wrongdoings during the insurgency. Quite a few police officers were allowed to confront militancy with whatever means they could possibly use in return for immunity and promotions, he added.

In a 2013 report, Christof Heyns, a member of the UN Human Rights Committee that recorded the situation in Punjab, said officers involved in human rights violations were promoted rather than held accountable.

He also said that delays in judicial proceedings constituted one of India’s most serious challenges and has clear implications for accountability.

Jagtar said that the investigation against Saini may reach a logical conclusion, but he is concerned about the pace of the legal proceedings. In such cases, he said, proceedings often move at a snail’s pace.

For instance, he added, in the 1990s when the SC acknowledged human rights violations in Punjab, people began to hope for the best. But things did not move forward as expected. “Although there are families who are still fighting the system, many have compromised with the situation whether under police threat or because of the indifferent attitude of the system,” said Jagtar Singh.

The fight is not over for people like Dalbir Kaur from Gurdaspur district. Dalbir lost her husband Sukhpal Singh in a 1994 police encounter, in which Inspector General of Police Paramraj Singh Umranangal, who was recently suspended in another case, is alleged to have been involved.

The case of Sukhpal Singh’s disappearance was registered in 2016, after Dalbir pleaded before the Punjab and Haryana high court in 2013 that the police team stage-managed an encounter with her husband to show that the dreaded terrorist Gurman Singh Bandala had been killed.

The high court appointed a special investigating team (SIT) led by DGP (Punjab State Power Corporation Ltd) Sidharth Chattopadhyaya, who filed an affidavit in the high court this March, stating that Bandala is alive and had been arrested in 1998 in some other case.

The SIT stated that it appeared that Bandala’s fake encounter registered in Ropar district and Sukhpal Singh’s disappearance from Gurdaspur are intricately linked, although the investigation is not over as yet.

Pardeep Virk, counsel for Dalbir Kaur, said she has been fighting a lone battle ever since her husband died. No effort was made by the state to identify who was the person killed if it was not Bandala. The SIT’s latest finding has given Dalbir new hope for justice.

Why it is important to uphold the rule of law

Punjab saw large scale human rights violations during the insurgency, but it is still widely believed that the state’s actions, whether wrong or right, restored normalcy to the region, making it a good thing overall.

Elsewhere in India, we have seen people cheering for police action, such as when the four accused in the infamous Hyderabad rape case last year were killed in a police encounter. The same people are now cheering the elimination of gangster Vikas Dubey.

Human rights lawyer Navkiran Singh told The Wire that the reason behind such thinking is the country’s tardy judicial system. It takes an average of 8 to 10 years, maybe even more, to get a case decided at a trial court.

“One must ask who is responsible for it,” said Navkiran Singh. “It is the government. It doesn’t appoint enough judges. It doesn’t ensure an effective witness protection programme. It creates monsters and then kills them for public sympathy.”

Despite the limitations of the system, the rule of law must be upheld at any cost, because if a country is not governed under the rule of law, there will be anarchy, added Navkiran. A person could be killed on the street if she is even suspected of committing a crime. No rule of law signifies an immature democracy.

If fake encounters and extrajudicial killings are to be stopped, said Navkiran, first of all, people should stop rejoicing in such killings. He argued that extrajudicial killings tend to happen when the government wants to distract people from the root causes of crime; when the state itself is in the dock.

According to advocate Arjun Sheoran, a counsel in several human rights cases in Punjab, the people who control the system are the ones who have created problems in the police, judicial and investigation departments. He added that the whole ecosystem of Bollywood masala movies, for instance, makes people believe that extrajudicial killings are fine.

Change will only come to the Punjab police when the Prakash Singh Committee report on police reforms is implemented, said Sheoran. “When we reform the police, we must ensure an adequate number of policemen and then separate departments for investigation,” he said.

The number of judges must also be increased, so that the judicial system works effectively and there must be proper compliance with the Supreme Court guidelines on encounter killings, he added. “Only the courts can declare an accused guilty or innocent,” said Sheoran. “This is the fundamental principle of our criminal justice system.”

Vivek Gupta is a Chandigarh-based reporter who has worked for several news outlets including The Hindustan Times, The Indian Express and The Tribune.

Read the original story here.