Exhuming Extra-Judicial Deaths in Punjab

A couple of weeks back, four former Punjab Police personnel were handed life sentences by a CBI court for extra-judicial killing of a teenager and the enforced disappearance of a youth in 1992. It took the Indian justice system 26 years to be able to punish the culprits yet Satnam Singh Bains, the lawyer who represented the complainants, believes it offered some solace to the families who fought back pressure and coercion. But what led a Barrister at Law to leave behind a comfortable lifestyle and come to India to pursue such cases of disappeared people in Delhi and Punjab? Bains narrates the journey:

I was born and brought up in London. I studied law in London and took my Bar exams from the same Inns of Court School of Law as Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. I began my practice with a leading chambers of human rights lawyers because my interest area as a lawyer lay in keeping a check on the unbridled power of the state.

As a student, what happened in Punjab during the militancy period and the 1984 massacre of Sikhs left an indelible impact. As with many of my generation, we were pained at the harrowing accounts of people who had suffered during those turbulent times, as well as thousands who were massacred at the hands of murderous mobs, while the State was a mute spectator. In 2007, with Jaswant Kaur, my wife, a fellow human rights advocate we came to India with a pressing need for accountability and redress for these gross human rights violations. I joined senior advocate Colin Gonsalves, known for his path-breaking work on human rights. At that time, Gonsalves was working on the Punjab Mass Cremations case which arose from the enforced disappearance and killing of human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra.

I found a unique opportunity to understand these cases and the systematic killings which had taken place in Punjab. This later led to a documentation project where we compiled cases of fake encounters, enforced disappearances and unclaimed and unidentified dead bodies across Punjab.

While working on these cases, we were so anguished that Jaswant and I decided to stay back in India and pursue them to a logical end. I still practice in London, but my emphasis moved towards my work in India.

After seven years of data collection and documentation our group, Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project, released our investigative report “Identifying the Unidentified” in 2017 and formed the basis for an Independent People’s Tribunal in Amritsar, which considered our findings. Despite the lapse of time we continued pushing as strongly as we could to help these families get justice.

While successive governments have remained silent on extra-judicial killings in Punjab during the militancy period, Jaswant Singh Khalra, a human rights activist, took up the cudgels against state oppression. He uncovered the records of Municipal Corporation of Amritsar city which contained names, age, addresses of many people who had been consigned to flames by police as “unclaimed unidentified” bodies. Khalra visited three cremation grounds in Punjab to find that there were 2,097 cases of unidentified bodies being cremated at government expense in Amritsar alone.

In 1995, Khalra was picked from his house and never found. His wife, Mrs Parmjit Kaur Khalra petitioned the Supreme Court which ordered the CBI inquiry not only into his disappearance but also in those 2,097 cases raised by him. The Supreme Court tasked the CBI to investigate these deaths and disappearances and to identify the unclaimed bodies. Out of the total, 1,514 bodies were eventually identified. The NHRC was delegated the task of identifying the bodies and it took them 16-17 years to identify, however we found that less than 2% were investigated by the CBI as criminal enquiries.

Even if those cases where the CBI had investigated and filed charge sheets, the accused police officers made various applications to further delay the proceedings. They claimed that as Punjab was under the Punjab Disturbed Areas Act at the time, this in essence gave them immunity and the right to abduct or kill innocent people. These cases were stalled for years because of misconceived arguments challenging sanction for prosecution. We worked towards vacating the various stays imposed with the matters reaching the CBI trial court and the trials in some of the cases resuming.

It is a matter of small solace that two such cases recently ended in the court handing out life sentences to four former Punjab Police personnel held responsible for staging a fake encounters of a teenager and disappearance of a youth. The first case was of 15-year-old Harpal Singh who was gunned down by police in 1992 accusing him of being a militant. They claimed that a total of 217 rounds were fired during the ‘encounter’. Despite claiming so many rounds of fire were opened at a 15-year-old, it was found that no bullet hit any of the police officials or their vehicle.

Their defence exposes their unaccountable position in those dark days. The real firearm was never recovered. None of the recoveries of arms or ammunition were shown as exhibits. The site map of the incident merely showed a dead body but no illustration of how the bullets were fired and in what direction. The clinching piece of evidence was that there were just two gunshots, to the head and under the eye, at the distance of three meters. It was a cold-blooded murder. And they thought they would get away with it.

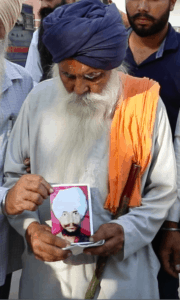

The second case was of an enforced disappearance where a 22-year-old man, Harjit Singh, was abducted from his house and never seen again. His father was detained for 22 days, he was released but nobody knows what happened to his son. An enforced disappearance is considered to be one of the most heinous crimes under International and Indian law, where the perpetrators are those tasked to uphold the law, the circumstances of the murder are never revealed and the victim’s body is never found or returned to the loved one. The conviction in the two cases are quite bold in terms of proving that there was something more organised and systematic behind these killings.

These two judgments are from a batch of 27 cases in which the Supreme Court had ruled that no sanction for prosecution was required. These cases are 27-28 years old. In these cases, there was never a political will.

However, the CBI courts have demonstrated that they have worked independently. If the investigation would have been assigned to the Punjab Police, these cases would not have got as far as they did.

The work ahead of us is enormous. There are volumes of cases pending; in many cases inquiry is still not completed and; there are thousands others where the inquiry was not even ordered. Ironically, the Supreme Court ordered investigations only into the cases related to just three cremation grounds investigated by Khalra. So the biggest injustice to people of Punjab ,who suffered similar fates but belonged to district outside of Amritsar, fell outside the purview of the CBI investigation.

When the NHRC was delegated the task to investigate these cases, they were flooded with claim forms from all across the state. Most of these claim forms were not rejected because the people were not ready to testify; these were rejected because their cases did not fall under those three cremation grounds. This was the biggest miscarriage of justice to the victims of Punjab.

Political parties misused the issue but only limited it to the elections. Whilst compensation and a rehabilitation package were given to the victims of terrorism, including benefits like jobs, free education and even pensions, the families who lost their kin to police repression have constantly remained deprived of rehabilitation and compensation.

Contrast the position of fake encounters with the rest of India. Take the recent death of an Apple executive , in the last few weeks who was allegedly killed when policeman fired at him for not stopping his car in Uttar Pradesh. The government immediately announced 25 lakh rupees as interim compensation and benefits before the investigation has begun. But in the present cases from Punjab, the court took decades to finally give justice and only granted compensation of one lakh rupees. These families faced all sorts of pressures, coercion but never gave up. It is the determination of these survivors that drives me.

In Punjab villages, people have long memories. They would narrate before you the incidents that took place in the 1980’s and 1990’s in a manner as if it happened yesterday. When you hear those stories, you can only feel anguished from deep within and the sense of injustice is palpable. We want to take forward the work of Jaswant Singh Khalra to its logical end in identifying those deaths and disappearances that continue to haunt thousands of families.

I strongly believe that for any state to function effectively, all its institutions are obliged to fulfil their functions and roles and uphold the rule of law. The decision of holding someone guilty can only be left to the courts. The job of the police is to gather evidence. But when the police becomes the executioner, the sanctity of the law is violated. The courts need to ‘zealously safeguard’ this sanctity. There is still a pressing and urgent need for a credible and independent Commission to investigate the mass extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances that took place across Punjab.