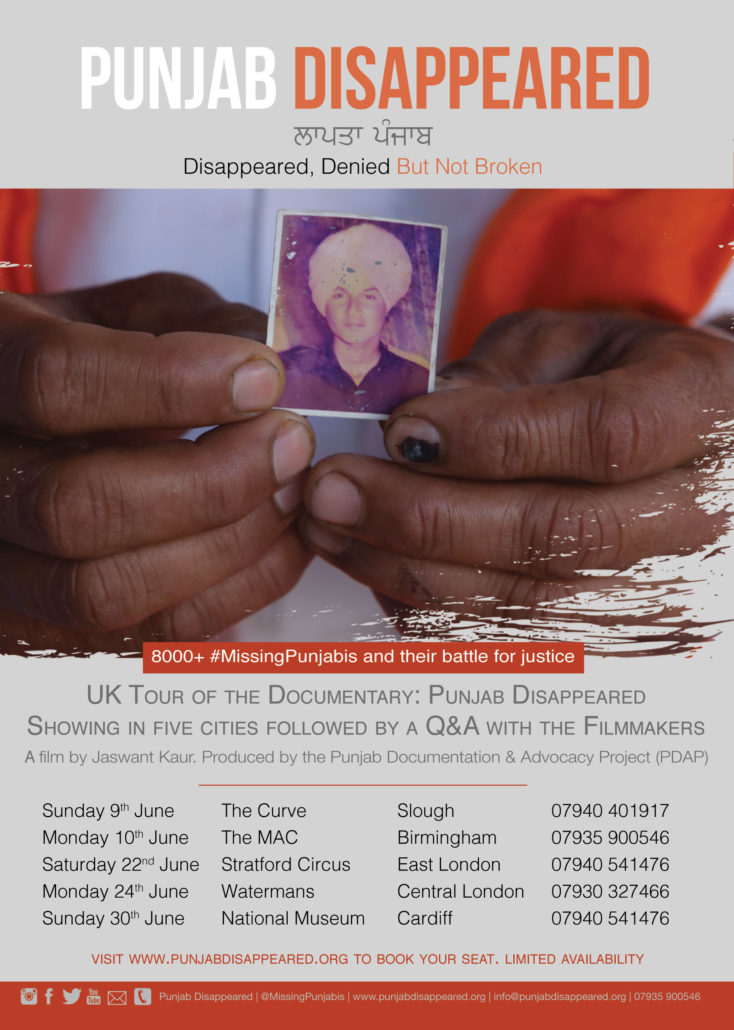

the untold story of the missing in punjab

The Background

From the 1980s until 1995 the north Indian state of Punjab was caught in a torrent of mass human rights violations. A political movement by the majority Sikh population of Punjab, for regional autonomy developed into a separatist movement for an independent Sikh state. Counter-insurgency operations by the Punjab police, the Indian army and paramilitary resulted in extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances of combatants as well as non-combatants. Thousands of those abducted remain missing to this day. They are known as the Punjab’s disappeared (Lapata).

The climax to the Sikh agitation was the Indian Army’s assault on the epicentre of the Sikh faith: The Golden Temple (Darbar Sahib), and its complex, on the pretext of flushing out Sikh militants. Known infamously as Operation Bluestar, it was ordered by the then Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi and its effects were cataclysmic. On 1 June of that year Mrs Gandhi ordered the military operation, ostensibly to ‘flush out’ armed insurgency inside the temple. The attack lasted until 8 June. A curfew was imposed on Amritsar and the media were removed to the borders of the district, thereby eliminating the possibility of any impartial reporting of events. Official reports put the number of deaths among the Indian army at 83 and the number of civilian deaths at 492, with more than 1000 casualties, but independent estimates vary. The former British Foreign Secretary, William Hague stated that, “as many as 3,000 people were killed including pilgrims caught in the crossfire”. Human rights groups have, however, suggested the number of those killed close to 5,000.

Five months after the attack, on the 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was shot dead in a retaliatory act by her Sikh security guards. Retribution for Mrs Gandhi’s assassination was swift and deadly. Whilst the world’s dignitaries gathered in the capital for her funeral, thousands of Sikhs were brutally massacred in Delhi and in other parts of the country, with Sikh homes and business destroyed. Sikhs were dragged from their homes and trains they were travelling in and butchered, their property, businesses and vehicles were set alight and destroyed. There are contemporaneous accounts of systematic sexual violence and gang rapes of Sikh women by the mobs.

In the immediate aftermath of 1984, a number of counter-insurgency operations were conducted in Punjab. Operation Woodrose followed Operation Bluestar in the same year; the ‘Bullet for Bullet’ policy between 1985-1988, Operation Black Thunder in 1988, Operation Rakhshak-1 in 1991, Operation Rakshak-2 and Operation Night Dominance in 1992. These operations were largely led by Punjab police, aided and assisted by central paramilitary forces including, but not limited to, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and the Border Security Force (BSF) and units of the Indian army. In Punjab, targeted ‘encounter’ killings and enforced disappearances were carried out in the name of national security by security forces with the protection provided by India’s draconian laws.

From the late 1980’s to early 2000’s a plethora of reports from regional and international human rights organizations emerged concerning the escalating insurgency and severity of human rights violations taking place in Punjab. The 2000’s saw entrenched criticism of the functioning of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the judiciary to investigation and adjudicate on cases mass state violence. Much has been written on the lawlessness and the impunity in which the Punjab police operated and the use of covert “death squads”.

The false claims of encounters of wanted fugitives and murder of innocent people was encouraged with the promise of promotions and a ‘catch-kill-reward’ policy, which incentivised killings and was part of a wider system of out-of-turn promotions for those conducting those ‘encounters’. The fortnightly magazine India Today reported at the time:

“The rush for claiming cash rewards is turning police into mercenaries…the department gives ‘unannounced rewards’ for killing unlisted militants…the operation of the secret fund is only known to a handful of senior police officers…records are maintained and erased after a few weeks…”

Typically, bodies of victims were taken for post-mortem and secretly cremated as ‘unclaimed, unidentified’. In most cases, the Punjab security forces claimed that they were the bodies of captured militants that were killed while trying to escape police custody, or militants that had ambushed police convoys and were killed in the cross fire during armed exchanges (encounters). Other abductees simply disappeared without trace. Our investigations conclude that the overwhelming majority of those fatalities were the result of unarmed victims being abducted from their homes and illegally detained and killed whilst in the custody of the security forces.

According to Indian Government figures there were around 25,000 fatalities during the conflict between the state and an independence movement. Human rights groups have maintained that the number is much higher. Exactly how many of these deaths were extra-judicial killings by state security forced has never been officially disclosed. When the of human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra uncovered evidence of thousands of secret cremations of victims of extra-judicial killings, he himself was abducted and brutally murdered by police. Several lawyers, journalists and human rights activists were also killed or disappeared at the height of the conflict.

The Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project (PDAP) started its investigations in 2008. The motivation in part was the massive under-documentation and recording of human rights violations during this period. What started as a formalised attempt to pool the collective experience, knowledge and data of the Punjab conflict steadily evolved into a systematic, investigation of enforced disappearances, extra-judicial killings and the secret disposal of dead bodies in cremation grounds across Punjab in the 1980’s and 1990’s. The original aims were, therefore, to document cases of those extra-judicially executed, enforced disappeared and arbitrarily detained in Punjab, India between 1978-1996, as strategically and comprehensively as possible.

Over a 10-year period the PDAP travelled extensively across Punjab visiting over 1,600 villages to record testimonies of eye witnesses and surviving victims whose loved ones had been abducted, tortured and disappeared. Starting in the Gurdaspur district, we undertook a detailed and exhaustive process, attempting to match and corroborate the identities of those killed with records of those cremated by the police and security forces as “unclaimed and unidentified” from records obtained from municipal cremation grounds, local administration and police reports.

In this way we were able to piece together complex and intricate fragments of information to reveal a sophisticated and systematic method of concealing victim’s identities and the secret disposal of their bodies. We repeated this process in 15 districts of Punjab’s 22 district. We were, able to access information of 6,140 cremations across 15 districts and over 1,400 police First Information Reports (FIRs) of alleged ‘encounters’ or ‘escapes’ from police custody, which contained a wide range of corroborative evidential information, enabling us to establish not only the identities of victims but also that of perpetrators and circumstances surrounding the deaths of thousands of victims. Our documented case studies revealed systematised disappearances, killings and illegal cremations having taken place in all 22 districts of Punjab in a broadly similar manner with relatively minor regional variations and practices.

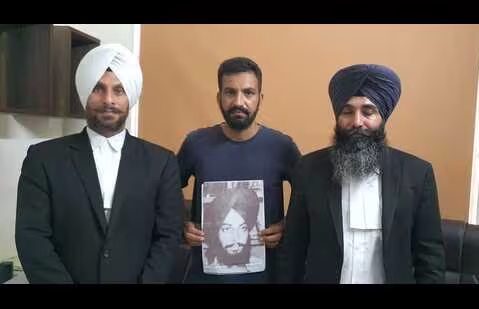

Through our investigations we have been able to confirm for some victim families what happened to the bodies of their’ loved ones. This has renewed their hope for justice. Determining the circumstances surrounding the loss of life of a loved one is an important step in both the mourning process for families and their long and painful journey to secure justice.

Human rights groups involved in investigating and documentation of the killings in Punjab over the past two decades have faced historic as well as contemporary challenges in identifying the victims. Families have also encountered numerous obstacles preventing them from obtaining information about the fate and whereabouts of their missing relatives. Under Indian and international law and standards, victims and families have enforceable rights and the Indian state has an on-going obligation to investigate these mass killings, disclose the identities of victims and prosecute those liable. The preservation and integrity of records is essential for supporting victims’ rights and bringing criminal prosecutions of perpetrators.

The overwhelming majority of the Punjab families affected have never had an official acknowledgment from the State confirming the death of their loved one. They have not been provided with death certificates of the deceased and no explanation for their disappearance has been offered by the authorities. They have had no access to justice or recourse to the courts to ascertain what happened, nor received any compensation. Conversely, many of those implicated in perpetuating these atrocities were promoted. They now hold high office and have benefitted from a culture of impunity when committing these acts, which has provided immunity from prosecution. The killers themselves, and those that ordered the killings have been, and continue to be, protected from any form of accountability.